DISCLAIMER: This paper has not been peer-reviewed by any publication, but only confirmed as valid as part of a university project by my former Open University tutor.

ABSTRACT Increasingly, people are more reliant on social media as the source of their news from platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. But these companies have not yet adequately addressed the lack of moderation of the quality of the news that is shared on them. This lack of action has led to the spread of misinformation at a scale and reach that was not previously possible with traditional media. In particular health-related misinformation can spread unchecked on these platforms and users are left with the responsibility to assess their veracity on their own. It is of particular interest, therefore, to investigate what are the variables that make one susceptible to health-related misinformation online, such as personality traits. To investigate if Dark Triad traits and Empathy Quotient can be predictors of General Susceptibility to Health-Related Misinformation Online (GenSHRMO), I conducted an electronic survey (n=122) where participants have been asked to complete a battery of questionnaires. Responses have been measured with both a 5-points Likert scale for the first 2 personality questionnaires and a 4-points Likert scale for measuring GenSHRMO. The data collected has then been entered into IBM SPSS for multiple regression (1-tailed) and correlation (2-tailed) analysis so that to determine the strength of the relationships between these variables and assess their validity as predictors. The results of this research show that only a weak relationship was observed between Psychopathy and GenSHRMO in the multiple regression analysis, but it was not present in the correlation analysis. No further statistically significant relationship between the other measured personality traits and the values of GenSHRMO was found. Findings, other significant correlations, and conclusions are discussed and explored in more detail in the Discussion section.

- Introduction

The widespread adoption of smartphones in the last 10 years coincided with the rise in popularity of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter all around the world (Ortiz-Ospina, 2019). These platforms, in turn, have become crucial tools for journalists on which to spread and promote their work (Newman, 2011). At the same time, people increasingly are getting their news from these platforms rather than traditional media outlets and hardly pay attention to their source (Sumida, et al., 2019). As the business model of social media platforms is based on user engagement so that to increase exposure to advertisements, they have been reticent historically to moderate the content that is being shared on their platform. The cost of entry that is responsible for the rise in their popularity also leaves the door open to the opportunity of misuse by bad actors and access to less than reputable sources of news. Consequently, social media platforms have been the main medium by which so-called “fake news” have been able to proliferate and spread widely online (Ortutay, 2016). For example, it has been reported recently that Facebook is still, as of the time of this publication, actively profiting from the engagement generated from pages and groups spreading health-related misinformation on vaccines (Graham-Harrison, et al., 2021).

As the responsibility to discern legitimate news from falsehood has been placed on its users, it is of particular interest for Psychology research to investigate what variables would make one susceptible to misinformation online, and which personality traits can be considered as predictors. For the scope of this research, the focus is on health-related misinformation specifically, as its spreading has far-reaching financial and social consequences (McKenna, 2019). Understanding the degree to which personality traits play a role in this could potentially help the development of tools and measures to combat the spread of misinformation on health-related topics.

The role of personality and motivation has been previously investigated, and it was found that the content of the message being shared holds less value than the action and outcome of the act of sharing (Chen, 2012). The author of the research noted that open-mindedness is positively related to susceptibility to misinformation and that “users that are aware of the falseness of misinformation, may still share it”. Chen suggests that this behaviour might be explained by it being motivated by seeking status and recognition within the person’s in-group. He also states that “the action of sharing, rather than the perceived accuracy and characteristics of the information being shared, is what matters most”. The author did not, however, seek to expand in his research on the possibility that Dark Triad personality traits (such as, for example, Narcissism) may play a role in the motivation for intentionally sharing misinformation on social media.

Motivation and personality types do not, however, account for the possibility that other factors may be at play such as the bandwagon effect, trust in the content and its source, fear of missing out and social media fatigue, where people find themselves lacking mental bandwidth to assess the veracity of what is being shared (Talwar, et al., 2019). Indeed, a more nuanced look at the motivation for sharing misinformation that does not require the invocation of personality type as justification has been proposed to explore this. Nonetheless, the role of personality traits cannot be discarded altogether as a personality is linked to motivational patterns of behaviour (Hansel & Visser, 2020). Since high trust in the content is linked to no hesitation from people sharing information that has not been verified, it leaves open the question as to which type of personality is more likely to be sufficiently open-minded to believe in certain kinds of misinformation as well as more prone to taking risks in sharing it and disregard the impact that sharing something that may be false may have on those exposed. After all, people are generally more likely to believe and share information that is consistent with pre-existing beliefs or worldview for both self-validation and confirmation (Lewandowsky, et al., 2012).

Dark Triad personality traits have indeed been found to be positively correlated to the susceptibility to health-related conspiracy theory in recent survey research (Malesza, 2020). The survey’s findings indicate a link between manipulative behaviour and hypersensitivity to being manipulated. These factors are then linked to higher susceptibility to a counter-narrative and consequently to the spread of misinformation to justify and reinforce the pre-existing belief, particularly in participants that scored high in Narcissism. Yet, another research’s finding suggests that highly empathetic individuals might place more importance on, or be more affected by, irrelevant information and thus, be more susceptible to misinformation just as well (Tomes & Katz, 1997). Moreover, findings from other research do suggest that narcissist personalities can take other people’s perspectives into consideration reflecting a potential for intervention (Hepper, et al., 2014). It is thus unclear which of these personality traits may be the most valid in predicting susceptibility to health-related misinformation online.

Based on the findings of previous research, it is possible to conclude that narcissistic personalities who are also susceptible to health-related misinformation online would manifest the following behaviour online: guided by an inflated sense of self and righteousness they would engage in the sharing of health-related misinformation masqueraded as an altruistic gesture that hides the seeking of social status and validation of existing beliefs. It is also possible that such behaviour is unlikely to be guided by malicious intent as people who genuinely hold beliefs that are based on health-related misinformation feel it is their duty to inform others, as it reinforces and validates their own belief. Similarly, people who show high empathy would also be more likely to spread health-related misinformation sharing the same beliefs and justification, and ultimately to the same end. Machiavellian personalities, on the other hand, would engage in similar behaviour knowingly ignoring the veracity of what is being shared for the self-serving purpose of status-seeking and validation, but still, perhaps see themselves as empathetic personalities.

Thus, the primary goal of this research has been to identify to what extent Dark Triad personality traits would predict participants’ susceptibility to health-related misinformation, alongside how they viewed themselves in relation to others, hence the Empathy Quotient questionnaire. The hypothesis this research is trying to prove is to assess if participants who show susceptibility to health-related misinformation online score highly in Dark Triad traits, in particular, that of Narcissism and Machiavellianism, and will also score highly in the Empathy Quotient test.

- Methodology

2.1 Sample

There are currently 53 million active social media users in the UK (Tankovska, 2021). To expect a 95% confidence level that the data collected would accurately reflect the general population, with a margin of error of 10%, the recommended sample size is 97 participants (Qualtrics, 2021). In total, 131 respondents provided consent to participate. However, only 122 fully completed the survey (completion rate: 93.02%). With 122 participants, the margin of error is close to 9%. Participants for this study were recruited primarily via the Open University EPW portal (99 participants, 75.57%), with others from social media platforms such as LinkedIn, Twitter, and Reddit (32 participants, 24.43%). The criteria for participation required participants to be at least 18 years old with no upper age limit; no other restriction prevented participation and participants were assumed to have been exposed to degrees of health-related news on social media platforms.

The majority of participants have identified as female (71.54%). The age of participants ranged from 18 to 63 years old with the majority (30.77%) falling in the 35 to 44 age group. No other demographic data from participants was collected other than gender and age. Participation in the survey was voluntary and the research proposal, alongside ethical considerations, was approved by the Open University D300 tutor.

2.2 Materials and Procedure

The core of the survey is composed of 2 personality questionnaires and 1 questionnaire to measure degrees of general susceptibility to, and the likelihood of spreading, health-related misinformation online.

2.2.1 Survey Administration

All three questionnaires were administered through the online platform Qualtrics (https://qualtrics.com). The survey was designed to be accessible from all known browsers for both mobile and desktop platforms. The survey consisted of a welcome page where participants were briefed on the nature of the project and the research’s goal, as well as provided with all the necessary information needed in order to give an informed consent. Participants were not allowed to proceed with the survey unless consent was confirmed. Participants were then asked for demographic identifiers of age and gender. This was followed by the battery of questionnaires, each on a dedicated page (3 pages in total), comprised of a total of 58 self-reporting items, concluding with a thank you note and a short debrief. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete. Participants were permitted to complete the survey without completing all items; they were also permitted to complete the survey up to a week from starting it. All the data for this research was collected over the entire month of March 2021 only.

2.2.2 Questionnaires and Scales

The first personality questionnaire is the “Short Dark Triad” by Paulhus and Jones (2013). It consists of 27 questions divided into 3 groups to measure traits of Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy. Participants are asked about their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 5 = “Strongly Agree”). The scoring of this questionnaire and its procedure have been kept as published at the source. This particular questionnaire was chosen for its concise length and because, according to its authors, “it provides efficient, reliable, and valid measures of the Dark Triad of personalities”. The internal consistency of this scale in the current sample was very good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.733).

The second personality questionnaire is “The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire” by Sprend et al. (2009). It consists of 16 statements and participants are asked to state the frequency of occurrence for each on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “Never”, 4 = “Always”). The scoring of this questionnaire has been kept as documented at the source. It aims to measure the Empathy Quotient of participants, and it was chosen for both its length and deemed validity as an instrument for assessing empathy. The internal consistency of this scale was low in the current sample but still valid (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.279).

The third questionnaire was designed specifically for the purpose of this research to measure the degree of susceptibility to health-related misinformation on social media and to assess the behaviour around sharing it. It consists of 15 statements where participants are asked about their level of agreement on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Agree”, 4 = “Strongly Disagree”). In particular, statements were designed to measure degrees of critical thinking on beliefs around health, trust in mainstream media messaging about health, trust in the opinion of medical professionals, and trust in the source of information on social media platforms. Examples of items are as follows: “I hold views and beliefs about my health that are ignored by the mainstream media”, “I trust my GP with concerns I have about views and beliefs about my health”, “I always check on the source of the articles I share that support my views and beliefs about my health”, “I do my own research to be informed about my health by reading on blogs of famous people I agree with” (see Appendix A for a full list of statements and scoring). Please note that other questionnaires may be better designed to measure this particular variable, but at the time of research design, none was found that was adequate. The internal consistency for this scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.643).

2.3 Data Analysis Strategy

As out of the 131 respondents only 122 completed the survey fully, the data from the 9 participants who did not fully complete it were removed from the dataset. The data file was further cleaned from not relevant information columns such as the time of completion and the date of administration.

All answers provided were measured on a Likert scale. For the “Short Dark Triad” and “The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire” personality tests, the value for each answer was kept identical to the source. As to the questionnaire on “susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation online”, values were attributed to each statement’s likelihood of matching what is being measured (see Appendix A for details).

The values of the Dark Triad personalities have been grouped into each of the measured traits: Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy. Furthermore, the sum of each personality value has also been grouped as a variable and named “Sum of Dark Triad Traits”. Each Dark Triad trait is considered as an independent variable for the purpose of this research’s data analysis, in addition to the value of the Empathy Quotient. The Sum of Dark Triad Traits variable has only been measured alongside the Empathy Quotient variable. Although the questionnaire on susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation contains statements to measure each of its two components, the sum of all values has been summarised to the variable “General Susceptibility to Health-Related Misinformation Online” (GenSHRMO). This value is considered the dependent variable in this research’s statistical analysis.

Analysis of the 6 assumptions needed to proceed with multiple regression was carried out. Two instances of multiple regression analysis (one-tailed test) were carried out: first, to investigate the strength of the relationship between each of the individual Dark Triad traits (Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy), the Empathy Quotient scores and GenSHRMO, and secondly to investigate the strength of the relationship between the total sum of the Dark Triad Traits score, the Empathy Quotient scores and the same GenSHRMO.

Two instances of two-tailed correlation analysis were also carried out so that to provide a complete overview of the strength of relationships between the aforementioned variables and to assure no bias in the data analysis. Furthermore, the distribution of the means responses and related standard deviation values were measured to provide an overview of the participants’ average responses. All statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS V25. Some calculations of averages have been carried out with Microsoft Excel.

2.4 Data validity

To assess whether the dataset collected is valid, 6 assumptions have been tested and confirmed to be met for multiple regression analysis. The scatterplots for linearity between IV and DV for all variables show homoscedasticity as variance along the line of best fit remains similar throughout; on the assumption of multicollinearity, the correlation table for the Pearson’s Correlation values for each IV does not exceed 0.8; the values of Durbin-Watson for each of the 2 models are of 1.88 and 1.89 respectively satisfying the assumption that the values of the residual are independent; the assumption that the variance of the residual is constant has also been met as the scatterplots of both models show equal homoscedasticity; the P-P plots of each model show that the majority of dots do lie close to the diagonal line thus satisfying the assumption that the values of the residuals are normally distributed; lastly, the assumption that no influential cases are biasing the model has also been met as there are no values that are above 1 in the column for Cook’s Distance statistics produced by SPSS onto the data file.

- Results

3.1 Participants and means with standard deviation distribution

The total number of participants that provided consent to proceed with the survey questionnaire was 131. Of these, only 122 completed it to 100% (completion rate: 93.02%).

On average, participants scored low on Dark Triad traits and Empathy Quotient but high on GenSHRMO. Here below are the details of each mean and corresponding standard deviation measure.

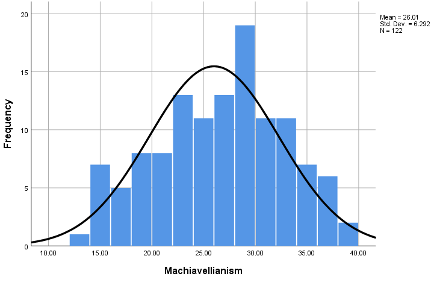

Figure 1

The mean score for the Dark Triad trait of Machiavellianism is 26.01 (N122, SD 6.29, max score 45. See Figure 1).

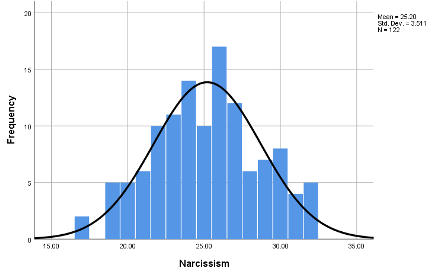

Figure 2

The mean score for the Dark Triad trait of Narcissism is 25.20 (N122, SD 3.51, max score 45. See Figure 2).

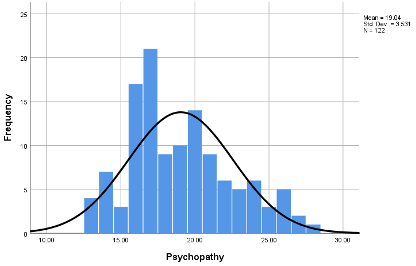

Figure 3

The mean score for the Dark Triad trait of Psychopathy is 19.04 (N122, SD 3.53, max score 45. See Figure 3).

Figure 4

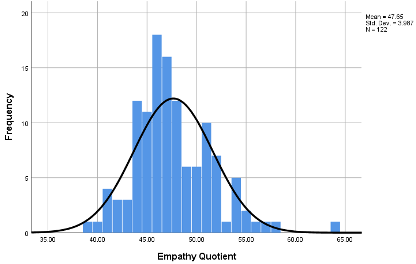

The mean score for the Empathy Quotient is 47.65 (N122, SD 3.99, max score 80. See Figure 4).

Figure 5

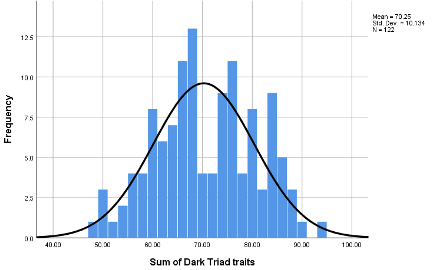

The mean score for the Sum of the Dark Triad Trait is 70.25 (N122, SD 10.13, max score 135. See Figure 5).

Figure 6

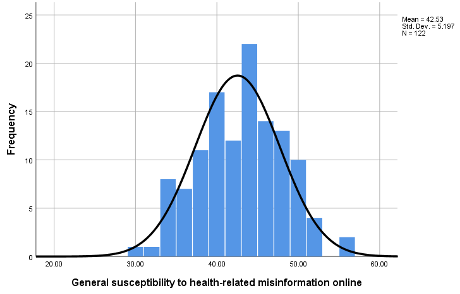

The mean score for the measure of GenSHRMO is 42.53 (N122, SD 5.2, max score 60. See Figure 6).

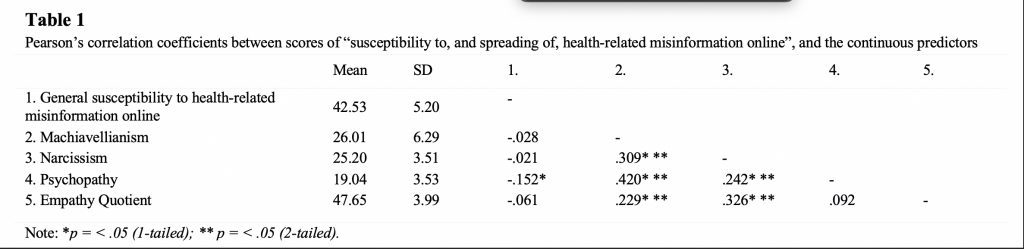

3.2 Continuous predictors

Summary of one-tailed and two-tailed Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the sum of the score for GenSHRMO, the Dark Triad personality traits and Empathy Quotient as continuous predictors are provided in Table 1. As shown in the table, there is only 1 statistically significant relationship between the Dark Triad trait of Psychopathy and GenSHRMO (p-value < .05) on the 1-tail test, possibly indicating a negative correlation between the two values. In the two-tailed test, however, the same correlation does not appear (p = .096). There are other statistically significant relationships between personality traits on both 1-tail and 2-tail tests, such as between Narcissism and EQ (p-value < .01) as well as Machiavellianism and EQ (p-value < .01).

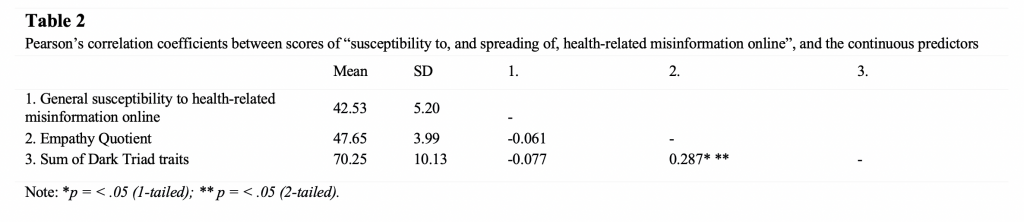

Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the sum of the score for GenSHRMO, Sum of Dark Triad Traits and Empathy Quotient as continuous predictors are provided in Table 2. As the table shows, there is no statistically significant relationship between neither the Sum of Dark Triad Traits nor the Empathy Quotient and the score of GenSHRMO. The only statistically significant relationship that exists is between the Sum of Dark Triad Traits and the Empathy Quotient (p-value < .01) in both 1-tail and 2-tail tests.

3.3 Multiple regression analysis

Two instances of multiple regression analysis were carried out. First, to investigate if the Dark Triad traits of Narcissism, Machiavellianism and Psychopathy, and the Empathy Quotient scores could be valid predictors of scores of “susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation online”. The result of the first regression analysis indicates that the model explains 28% of the variance and that it is not a significant predictor of participants’ susceptibility to and sharing of health-related misinformation online, F(4,117) = 0.854, p = 0.494. None of the measured personality traits contributed significantly to the model (Machiavellianism B = 0.42, p = 0.623;Narcissism B = 0.040, p = 0.788; Psychopathy B = -0.256, p = 0.089; Empathy Quotient B = -0.086, p = 0.499).

The second instance was to investigate if the Sum of Dark Triad Traits and the Empathy Quotient scores could be valid predictors of scores of “susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation online” as well. The result of the second regression analysis indicates that the model explains only 8% of the variance and that it too is not a significant predictor of participants’ susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation online, F(2,119) = 0.460, p = 0.632. Equally, neither the score of the Sum of Dark Triad Traits nor the Empathy Quotient contributed significantly to the model (Sum of Dark Triad Traits B = -0.33, p = 0.496; Empathy Quotient B = -0.56, p = 0.655).

4. Discussion

The average participant of this survey scored slightly above 50% of the scores for both Dark Triad traits of Machiavellianism (65%) and Narcissism (63%) whilst scoring just below 50% on the score of Psychopathy (47.5%). On Empathy Quotient, the average participant scored 58.31% of the total score, whilst on GenSHRMO – 75.88% of the total score.

In the 1-tail multiple regression analysis carried out to investigate the strength of the relationships between the individual Dark Triad traits of Machiavellianism, Narcissism, Psychopathy, and Empathy Quotient against participant’s susceptibility to, and the likelihood of sharing, health-related misinformation online, the result indicated that the only marginally significant trait that could be a valid predictor is that of Psychopathy with a p-value of .048. However, on the 2-tail correlation analysis test, this statistically significant relationship is no longer present (p= .096). This conflicting result would suggest that although a relationship is present, it is not sufficiently strong to meet the criteria for being statistically valid to be used as a predictor for participants’ susceptibility to health-related misinformation online. Similarly, both the 1-tail and 2-tailed correlation analysis tests carried out to investigate the strength of the relationships between the Sum of Dark Triad Traits, Empathy Quotient and participant’s susceptibility to health-related misinformation online have shown that neither personality traits are valid predictors. With regard to the goal of this research, therefore, the hypothesis that people who scored high in Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Empathy Quotient would also be more likely to be susceptible to, and be spreading, health-related misinformation is not validated by the survey’s results.

Of note, however, is that data on both 1-tailed and 2-tailed multiple regression and correlation analysis show that there is indeed a statistically significant relationship between the Dark Triad trait of Narcissism and Empathy Quotient with a p-value of .00 for both, and that of Machiavellianism and Empathy Quotient with a p-value of .006 in the 1-tailed and .011 in the 2-tailed test. Similarly, both 1-tail and 2-tailed multiple regression and correlation analysis show a statistically significant relationship between the Sum of Dark Triad Traits and Empathy Quotient with a p-value of .001 for both tests. The Pearson’s Correlation values do indicate it is a negative correlation in both cases, where the higher score of Narcissism and Machiavellianism would be related to lower scores of Empathy Quotient. Interestingly, the results indicate no statistically significant relationship between the trait of Psychopathy and Empathy Quotient in neither 1-tail nor 2-tailed test.

The rationale that guided this research was based on the assumption that participants would respond more truthfully to the Dark Triad personality test and provide more embellished versions of themselves in the Empathy quotient test. The expectation was that the scores of Narcissism and Machiavellianism would positively correlate to the Empathy Quotient and consequently also positively correlated to the scores of GenSHRMO. The hypothesis was that someone with an inflated sense of self, who also has low considerations of and for others, would nonetheless portray themselves as being someone who cares about others. This factor, related to a hypersensitivity to manipulation, higher susceptibility to a counter-narrative consequently leading to the spread of misinformation to justify and reinforce the pre-existing belief, provided the foundation for the research question. The results of this research, however, do not support this model.

There are a few considerations to make that could explain why the result does not support the proposed hypothesis. Firstly, it is the nature of self-reporting of surveys: as participants were aware that the first personality questionnaire pertained to Dark Triad personality traits, there is a possibility that the better-than-average effect may have influenced participants responses. Even though responses are fully anonymous, people could potentially seek to reinforce their self-image in a positive light. Research has shown that people who compare themselves with an average peer would consistently evaluate themselves more favourably than them (Alicke, et al., 1995). Some of the statements in the Short Dark Triad Test may indeed focus the attention of participants on less favourable traits such as the following: “You should wait for the right time to get back at people”, “I know that I am special because everyone keeps telling me so”, “I insist on getting the respect I deserve”, “Payback needs to be quick and nasty”, and “I like to pick on losers”. Thus, it is possible that consequently, participants would rather portray a more likeable version of themselves to themselves and therefore not be able to truthfully assess their level of agreement to such statements. It must be noted, however, that the average score of Empathy Quotient is 58.31%, which does contradict such hypothesis, as for it to be true the average score should have been perhaps higher.

Secondly, the pool of voluntary participants could have had an unexpected impact on the data collected. As the majority of respondents were recruited from the Open University portal that is only available to its students (n99, 75.57%), it is possible that such a pool of participants may not necessarily adequately represent the segment of the population that would likely fit the criteria of the proposed hypothesis and the general population of social media users at large.

It must be noted, however, that the average score for general susceptibility to, and sharing of, health-related misinformation online is quite high (75.88%), which is a surprising result considering the composition of the majority of participants. As most students that had access to the EPW portal would have been engaged in their own scientific research, a certain degree of critical thinking skills that ought to lead to a lesser susceptibility to misinformation online, specifically health-related, was expected. Of statements that scored surprisingly high, of note are the “Homeopathic Doctors are better informed than Medical Doctors” with a total of 108 participants (88.52%) scoring an average of 3.5, and the “Famous people are better at informing me about my health than scientists” with 106 participants (86.82%) scoring an average of 3.7. This does suggest that the majority of participants do indeed display a degree of susceptibility to health-related misinformation in general. It is possible, however, that the questionnaire used to measure GenSHRMO may not have been sufficiently adequate to measure what it was meant to. Some of the statements may be a reflection of my own beliefs and prejudices about what would make one susceptible to health-related misinformation.

The results of this survey do, nonetheless, challenge the 1997 findings by Tomes & Katz that highly empathetic individuals would be more susceptible to misinformation, as the high score for GenSHRMO did not correlate with a high score of Empathy Quotient. Furthermore, as the previous research conducted by Malesza in 2020 has suggested, a stronger relationship between Dark Triad traits and GenSHRMO should have been present in light of her findings that linked manipulative behaviour to hypersensitivity to being manipulated. Only the data of the 1-tailed test shows a weak link in the relationship between Psychopathy and GenSHRMO, which would give merit to the previous research’s findings. As previously mentioned, however, that statistical significance is not present in the 2-tailed test.

The results of the data collected do show a strong statistically significant relationship between individual Dark Triad traits and Empathy Quotient, as well as the Sum of Dark Triad Traits and EQ, which suggests that the overall results are a fair representation of the participants’ personalities rather than the outcome of subconscious manipulation from their part. Indeed, the Pearson’s coefficient table shows a negative correlation between the variables, as it would be expected by participants answering truthfully. This research, therefore, supports the notion proposed in Talwar et al.’s paper that a more nuanced look, which does not require the invocation of personality type as justification, is required to investigate what makes people susceptible to health-related misinformation in the first place.

Future research into this matter could benefit from a more ample pool of participants, not composed of mainly university students, that is more adequately representing the general makeup of social media users. The low score of Empathy Quotient would suggest that this personality trait is not as important as initially hypothesised to predict people’s GenSHRMO and could be removed from the proposed model. Furthermore, it is possible that a larger and more comprehensive Dark Triad test may help in providing a more accurate assessment of participants’ personalities, for example, by including reverse wording. It would be interesting to confirm which of the three main Dark Triad traits is a more likely predictor of GenSHRMO, as this research did suggest a possibility of correlation between GenSHRMO and Psychopathy. Although, it must be acknowledged that one’s susceptibility to health-related misinformation seems to be more rooted in people’s beliefs and views of the world rather than depending on their personalities and predispositions towards others. Therefore, a qualitative approach may be more appropriate to investigate this subject matter alongside a survey so as to capture the nuances of the subject matter.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, guided by previous research, the goal of this project was to prove a positive correlation between Dark Triad personality traits, Empathy Quotient, and people’s general susceptibility to, and the likelihood of spreading, health-related misinformation online. The results of this research do not support the hypothesis that people who scored high in both Dark Triad traits of Narcissism and Machiavellianism would also score high on Empathy Quotient and that these could be used as predictors of the score of GenSHRMO. Instead, the data indicated a small but statistically significant correlation between Psychopathy and GenSHRMO in the 1-tailed test, which was not present, however, in the 2-tailed test. This particular finding should be analysed in future research with a deeper investigation into Dark Triad personality traits, also including a provision for a qualitative perspective for a more nuanced and complete understanding of what makes people susceptible to, and what makes them spread, health-related misinformation online.

References

Alicke, M. D. et al., 1995. Personal contact, individuation, and the better-than-average effect.. APA PsychNet, 68(5), pp. 804-825.

Chen, X., 2012. The Influences of Personality and Motivation on the Sharing of Misinformation on Social Media. s.l., iSchools.

Graham-Harrison, E., Jackson, J. & Heal, A., 2021. Facebook ‘still making money from anti-vax sites’. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jan/30/facebook-letting-fake-news-spreaders-profit-investigators-claim

[Accessed 16 April 2021].

Hansel, R. & Visser, R., 2020. Does personality influence effectual behaviour?. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(03), pp. 467-484.

Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M. & Sedikides, C., 2014. Moving Narcissus: Can Narcissists Be Empathic?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(4), pp. 1079-1091.

Jones, D. N. & Paulhus, D. L., 2013. Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A Brief Measure of Dark Personality Traits. Assessment, 21(1), pp. 28-41.

Lewandowsky, S. et al., 2012. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), pp. 106-131.

Malesza, M., 2020. The Dark Triad and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories About the COVID-19, Warsaw: The University of Economics and Human Sciences in Warsaw.

McKenna, M., 2019. The True Dollar Cost of the Anti-Vaccine Movement. [Online]

Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/anti-vaccine-movement-true-cost/

[Accessed 24 April 2021].

Newman, N., 2011. Mainstream Media and the Distribution of News, Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Ortiz-Ospina, E., 2019. The rise of social media. [Online]

Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/rise-of-social-media

[Accessed 16 April 2021].

Ortutay, B., 2016. https://apnews.com/article/1fc42b60a63e49568f0b3707a36c6b23. [Online]

Available at: https://apnews.com/article/1fc42b60a63e49568f0b3707a36c6b23

[Accessed 16 April 2021].

Qualtrics, 2021. Sample Size Calculator. [Online]

Available at: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/calculating-sample-size/

[Accessed 14 April 2021].

Spreng, N. R., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A. & Levin, B., 2009. The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale Development and Initial Validation of a Factor-Analytic Solution to Multiple Empathy Measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(1), pp. 62-71.

Sumida, N., Walker, M. & Mitchell, A., 2019. News Media Attitudes in France, Washington: Pew Research Center.

Talwar, S. et al., 2019. Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Volume 51, pp. 72-82.

Tankovska, H., 2021. Social media usage in the United Kingdom (UK) – statistics & facts. [Online]

Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/3236/social-media-usage-in-the-uk/

[Accessed 14 04 2021].

Tomes, J. L. & Katz, A. N., 1997. Habitual Susceptibility to Misinformation and Individual Differences in Eyewitness Memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, Volume 11, pp. 233-251.

Appendix A

Questionnaire and scoring on General susceptibility to and sharing of health-related misinformation online.

| Susceptibility to (ST) – Sharing of (SO) | strongly agree | slightly agree | slightly disagree | strongly disagree | |

| 1 | I hold views and beliefs about my health that are ignored by the mainstream media. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | Homoeopathic Doctors are better informed than Medical Doctors. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | I regularly engage with news that discusses in a negative light something that I believe in, about my health. (ST) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | I trust my GP with concerns I have about views and beliefs about my health. (ST) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | I often disagree with health-related news presented by the mainstream media. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | I am part of one or more groups on social media where I feel free to discuss my views and beliefs about my health. (SO) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | I share articles on social media the support my views and beliefs about my health. (SO) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 8 | I always check on the source of the articles I share that support my views and beliefs about my health. (SO) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | I do my own research to be informed about my health by reviewing peer-reviewed scientific publications. (ST) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 | I do my own research to be informed about my health by reading blogs of famous people I agree with. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | Famous people are better at informing me about my health than scientists. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 12 | I do remove an article I have published on social media if and when I find it was misleading. (SO) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | I search online for information about my health from multiple sources. (ST) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | Articles that make me feel a strong emotion about my health are more valid than science articles about the same subject. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 15 | Articles that promote my existing views and beliefs about health from people I know are more valid than articles from scientists that contradict them. (ST) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |